The Language of AI

John McCarthy is credited with two major contributions to Computer Science. The first is the term “Artificial Intelligence”, and the second is the programming language LISP. In part due to this entwined history, and in part due to its particular strength, LISP was long though of as the language of AI, but it’s more than that — it’s not an exaggeration to say that pretty much every programming language in use today borrows from LISP to a greater or lesser degree, and LISP itself is still in alive and well in various forms. There’s a lot of history to delve into, but recently I decided to try out something almost equidistant from today and LISP’s origin in 1960: LISP on the Acorn Electron.

This isn’t actually the first time I’ve used that particular implementation. As a child in the 80s, I remember being intrigued and picking up a copy on cassette from a market stall for a few pounds. Unfortunately, the experiment was short-lived, as the software didn’t come with any documentation. I fumbled around trying to get the enigmatic “Evaluate:” prompt to do something useful, but didn’t get anywhere, and soon moved on to less obtuse pursuits.

A few decades later, and I’m returning to it better prepared. Not only do I have both a reasonable grasp of the theoretical foundations and a degree of practical experience with a variety of LISPs, I also managed to find a decent second-hand copy of LISP on the BBC Microcomputer by Arthur Norman and Gillian Cattell, the very documentation I was missing the first time round. So, with the barriers out of the way, what is LISP on an 80s micro actually like?

To my surprise, pretty good. The Electron is a far cry from the Lisp Machines that were its contemporaries, or the mainframes and minicomputers that LISP grew up on. In particular, it has little RAM, and a CPU built around bytes rather than words. To fit inside these constraints, Acornsoft LISP is an interpreter rather than a compiler (as more fully-fledged LISPs tend to be), and it only includes the essentials — so no arbitrary-precision arithmetic, no macros, no conditions. What’s left, however, is a flexible and well-thought-through environment that captures the flavour of LISP, especially for learning and exploration.

This environment is both interactive and transparent, in the best traditions of the REPL1. This provides the immediacy of BASIC with a far more structured and powerful underpinning. An upside of the interpreter approach is that it puts the equivalence of code and data, one of LISP’s strengths, front and centre. Functions are just lists starting with the symbol LAMBDA, and can be manipulated as such with no intermediaries.2

This transparency forms the basis of one of the more interesting aspects of the system: the interactive code editor. For most people familiar with LISP, “editor” immediately conjures up the image of Emacs and similar editors, but this isn’t that. It’s more akin to the long-obsolete concept of interactive line editors such as ed3 and ex4. Instead of moving a cursor around a visible display of the source code, you issue a series of commands to manipulate it, and then print out some or all of the modified text.

What makes the Acornsoft LISP editor different is that, unlike ed and ex, it’s a structured editor — instead of manipulating lines of text, the commands manipulate lists. As functions are, like pretty much everything else, just nested lists, this provides an immensely powerful way to both navigate and edit the code, with the added bonus that introducing syntax errors is impossible. It’s somewhat akin to block-based programming languages like Scratch, and while it takes a little getting used to it’s a great interface when it does click, so much so that I find myself wondering what a modern take would be.

The documentation is equally inspiring. Norman and Cattell start with a thorough and well-paced walk through the fundamentals, and then move on to some more substantial examples. The first, as is required by law in any book on LISP, is a LISP interpreter, followed by some other LISP-related facilities such as a pretty printer, a correct-but-slow implementation of arbitrary precision integer arithmetic, and the internals of the aforementioned structured editor. They then broaden out to more general parsing, evaluation and generation of machine code, demonstrating the suitability of LISP for building compilers (and the authors’ interest in that field). The chapter is rounded off with a bare-bones implementation of a text adventure. This is clear, general and extensible, and shows off the expressiveness and power of LISP.

So, after all that, is Acornsoft LISP a good choice for programming the Electron? If your aim is to produce something for others to use, probably not — aside from the fact that they’d also need to have the interpreter, the overhead is likely to be too much. With such limited resources, you usually want to squeeze as much performance out of the hardware as possible, and that’s not where LISP’s strength lies. However, if you’re programming a one-off solution for yourself, or exploring a problem interactively, it seems like an excellent choice. A modern analogue would be something like Jupyter notebooks. Not bad for a little computer from the early 80s, even if I didn’t realise it at the time. I’m glad I revisited it.

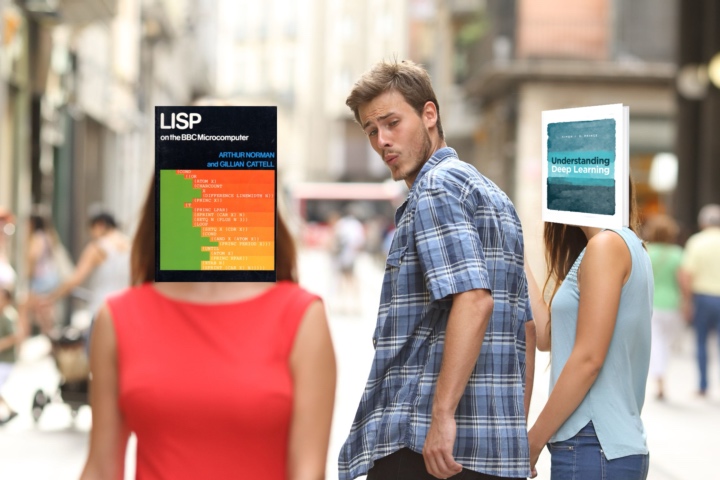

The original photograph behind the Distracted Boyfriend meme is by Antonio Guillem. The books pictured are LISP on the BBC Microcomputer by Arthur Norman and Gillian Cattell, referenced in the text, and Understanding Deep Learning by Simon J. D. Prince, a somewhat more recent take on AI.

-

REPL: Read-Eval-Print Loop, the interface by which you can type in an expression and see the result of evaluating it. This is nearly ubiquitous for modern languages, but was pioneered in LISP, and and name comes from the implementation in early LISP:

(loop (print (eval (read))))(read it from the inside out). [back] -

Interestingly, Acornsoft LISP is a Lisp1 like Scheme, rather than a Lisp2 like Common LISP and its immediate ancestors. [back]

-

edis the standard text editor. [back] -

Now better known for the visual editing mode that was built on top of it,

vi. [back]