Getting Ink

I’ve long been an enthusiastic user of the Kindle — so long, in fact, that my first one had a keyboard. While I’m conscious of the downsides of Amazon’s dominance of the market, and the limitations of a closed device and ecosystem, the user experience of buying and reading books on Kindle is for me a good trade-off. I still enjoy printed books (my reading is approximately 50/50), but I miss the ease of highlighting and annotation, plus the ability to pick up where I left off on my phone, or even in the Audible audiobook. The thing that seals the deal, though, is the eInk screen — especially when paired with a decent frontlight (as it is on all modern e-readers), it offers a great way to access all of this convenience while still being a change of pace from the light-emitting screens I spend much of my time looking at.

My relationship with the iPad is somewhat more mixed. For a long time, I, like many people, couldn’t quite figure out where it fit into a life that already had an iPhone and a laptop. The form factor was appealing enough that I tried to figure out how to use it for “real work”, but the advent of Apple Silicon made it clear that what I was actually after was the iPad’s SoC (and the resulting benefits) in a Mac.

The one thing I did find it consistently useful for was reading. Not fiction — the Kindle knocks it into a cocked hat for that — but things like articles, papers and so on. When compared to a phone screen, the iPad’s additional real estate makes all the difference, especially for documents laid out for print.

Over the years I’ve experimented with a wide array of apps and services to wrangle reading material on the iPad. At present, and for a bit over a year now, I’ve been pretty much all-in on Readwise Reader. This provides a combination of read-later, RSS feeds, annotation and archiving that fits the way I want to work, and now accounts for maybe 80% of my iPad use (probably 95% or more of my non-video use). I’ve disabled all notifications on the device, and removed all apps from the Home Screen. The iPad is my quiet place, one where I can go to read.

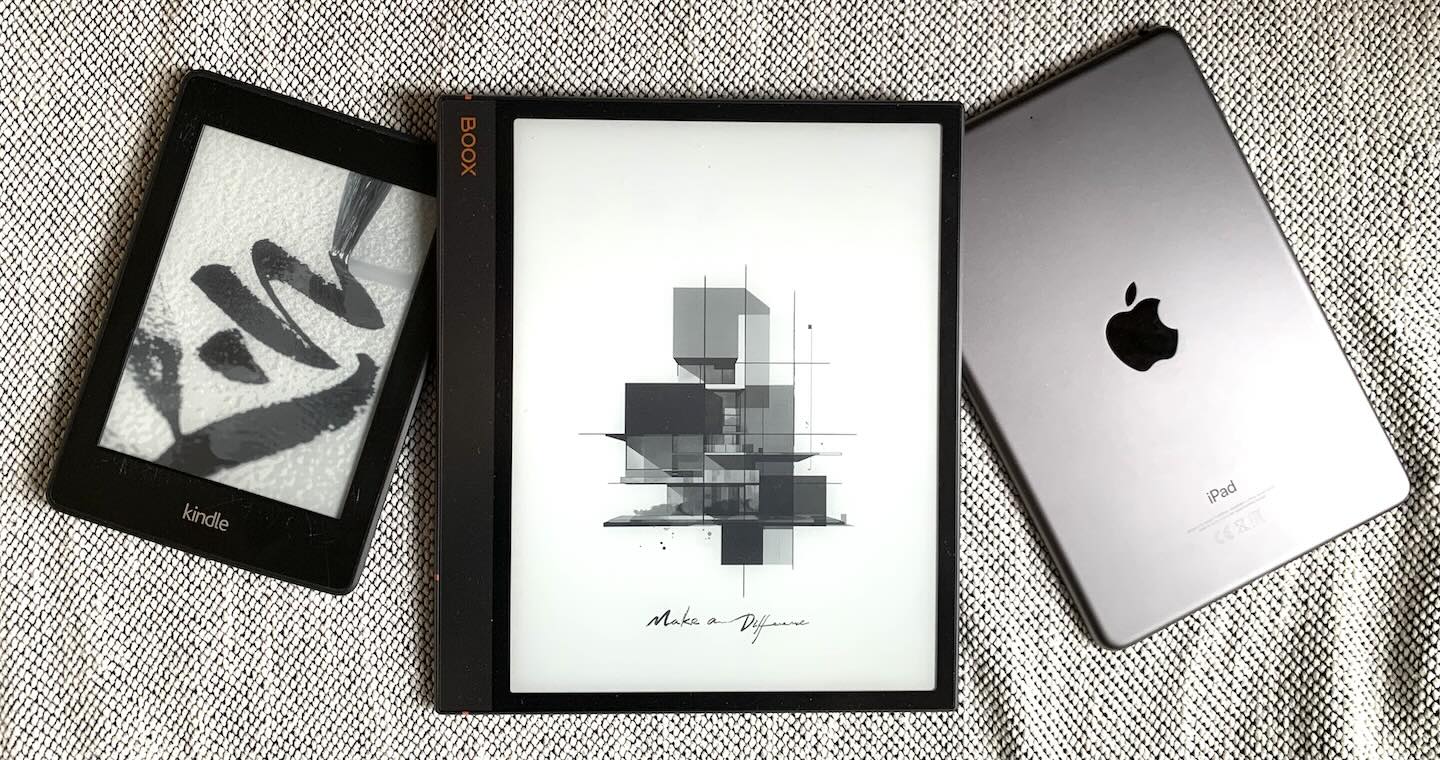

Given this clarity of purpose, I began to wonder whether the iPad was in fact the best device to fulfil it. A couple of years ago, I noticed the emergence of a new category of devices — eInk tablets. Led by the reMarkable, these go beyond the functionality of an eReader like a Kindle, and offer more general applications, often with an emphasis on hand-written note taking. I wasn’t particularly interested in that aspect, but the promise of a relaxing screen and distraction-free environment was appealing. I came across the Onyx Boox Note Air 3, with its decent-sized screen and ability to run standard Android apps, and decided to give it a go.

The device gives a good impression right out of the box. Its metal construction is up there with Apple’s; it felt solid in the hand, and I didn’t notice any flex at all. The 10.3” eInk screen is akin to the standard size iPad (a step up from my iPad Mini), with narrow bezels on three sides, and a wider one down a long edge to give a natural place to hold. Overall, it seems like a well built, high end device. If I had a reservation about the physical feel of the hardware, it’s that it’s too well-built. The Kindle’s lighter (and, let’s face it, cheaper) plastic construction makes it a very comfortable device to use for long periods, and one that I have no compunction about tossing into a bag. The Boox is definitely more akin to an iPad in this regard.

The software is essentially a custom shell on top of Android, but crucially it includes Google Play, making it much closer to “normal” Android that the Kindle Fire, the only other Android-based platform I’ve used in earnest. Setting up wasn’t particularly hard, and the note-taking functionality that is pitched as the tablet’s major use case seems to work well. The bundled stylus feels good and works well, and I was impressed by the lack of egg freckles — the hand writing recognition worked near perfectly on my very messy cursive, straight out of the box. The switch between drawing, handwriting and text was often clunky, but no worse than any similar note-taking application I’ve used on the iPad, and better than many.

However, as mentioned, I’m not here to take notes. Boox does offer its own book store and RSS reader, but I had zero interest in dipping into yet another ecosystem for either of these. The attraction for me was the Play Store icon, which allowed me to install Readwise and tap into the tools I already use. Unfortunately, this was also where things started to hit trouble.

Installation was easy enough, and I was soon exploring my feed and library. Immediately, it became apparent that the experience had been designed for fast-updating, colour screens, and while the Boox did its best to compensate, the experience fell very short. A variety of screen refresh strategies are available, and it’s possible to select different ones for each app, but even when you go to the effort to do so there’s only so much improvement to be had. Some things that are natural and pervasive on LCDs simply don’t translate to eInk.

The main culprit is scrolling, perhaps the most common navigation paradigm in modern phone and tablet interfaces. On eInk, the display is an unreadable blur when in motion, and even when it stops there’s usually ghosting and smudging left behind. More generally, modern interfaces tend to make extensive use of animation to illustrate transitions (and disguise delays). This is often derided, but serves a useful purpose and is usually a net win on conventional displays. Here, it’s not.

In full awareness that this was something of an experiment, I persevered, and managed to make some improvements. By tweaking settings, and moving to the Beta version of Readwise, I was able to smooth off some of the rough edges. Enabling pagination as opposed to scrolling in the reading view made the biggest difference. However, the experience was still far from ideal. I also downloaded the Kindle app, which offered a pretty direct comparison with my previous eInk experience. Even there, it didn’t quite work as I’d like, as we’re talking about the app designed for phones and conventional tablets, as opposed to eReaders.

Ultimately, it comes down to the fact that the mainstream Android platform isn’t designed for this kind of display. Even with the best efforts of Readwise to accommodate the differences (I don’t expect the Kindle team were trying very hard in this case), the UI conventions and workflows just don’t translate. It might be possible to design, from the ground up, an application platform that worked with eInk as a first class citizen, but perhaps not. Maybe eInk is inherently too specialised for a platform approach to make sense. The Kindle (or Kobo, or reMarkable) can concentrate on doing one task well, rather than diluting its unique advantages by trying to do things it isn’t cut out for.

In the end, I returned the Note 3. It was an interesting experience, and I’m glad I tried it, but I found that, for my use at least, there are too many compromises to justify working it into my digital life. For the time being, I’m sticking with the iPad — it seems to be a better solution to my particular use case. However, I hope that Onyx and others carry on experimenting with new types of device such as this. What we have today is most definitely not all that there ever can be.